Michele Erwin is a mother on a mission. After experiencing the struggles of traveling by air with her son, who has spinal muscular atrophy, she had a “call to action” moment–something had to be done to make air travel accessible to the disabled community. Michele soon learned that there was not a single organization out there even talking about wheelchair accessibility on airplanes.

Michele’s mission took flight when she founded All Wheels Up in 2011. All Wheels Up is a research organization that advocates for wheelchair accessible air travel and crash tests wheelchairs for commercial flight.

While still working full time in the fashion industry, Michele’s dedicated focus has brought together key players from air industry, wheelchair manufactures, and disability rights organizations to discuss the idea seriously and in practical terms.

Denise Miller: How did you get involved going from fashion design into airplane wheelchair accessibility design?

Michele Erwin: I have a son who has spinal muscular atrophy or SMA. It’s a neuromuscular illness very similar to ALS, but it affects children. It’s a muscle-wasting illness. He uses a wheelchair.

I was traveling with him when he was young and learned very quickly how difficult it was to travel with a wheelchair. On a very frustrating flight, I was thinking, how is he going to do this when he goes off to college or has a career and needs to travel for work? It dawned on me–how do people travel by air with wheelchairs?

When I got off that flight, I started doing research and learned that there was not a single organization out there even talking about wheelchair accessibility on airplanes. There was no one to call, no group to join, no one to share frustrations.

It hit me then that something’s got to change. To be honest with you, I wasn’t really looking to create a company; I wasn’t looking to invest my life to trying to move this enormous air travel elephant! (laughs)

Miller: (laughs) What did you decide to do? Where did you start?

Erwin: I decided that I was going to stick my flag in this issue and say, “OK, this is what I want to work on.” I decided to move accessible air travel forward–more than the small box that the airlines regulated it in. The airlines general perspectives were “we’ve made it as accessible as we can,” and expected the disabled community just be happy and accept that they tried to accommodate us.

Looking around me, I saw many modes of transportation offered disability travelers accessibility, like, lifts on buses, trains, wheelchair accessible cars, and more. I knew it was time make air travel as accessible as any other mode of transportation to the disability community. So in 2011, I started All Wheels Up.

Miller: So what is All Wheels Up? Is it a business or a non-profit organization?

Erwin: All Wheels Up is a non-profit. We don’t make anything. We don’t sell anything. We do not design anything. We are set up like a cure-based nonprofit. We advocate for wheelchair spots on airplanes. We advocate for funding in Congress and for things to happen.

We learned in 2011 that wheelchairs and wheelchair securement systems that are currently on the market today pass a 20g crash test. The airplane seats that you and I sit in today are tested at 16gs. Just putting these numbers out there, it begged the question of why couldn’t there be a wheelchair spot on airplanes if wheelchairs and tie-downs already go through the rigorous testing that they do.

Miller: Tell me about the wheelchairs spots and locking systems. How does it work?

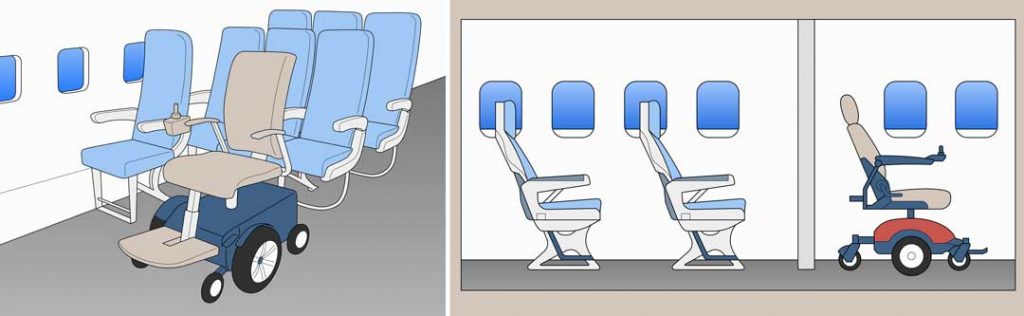

Erwin: Our proposal is for those who use electric wheelchairs, as well as properly modified manual wheelchairs, to independently maneuver themselves onto the plane into the designated wheelchair spot. The wheelchair passenger could enter by either the front or rear entry of the plane. The passenger can fly comfortably and safely in their own chairs.

We have researched the crash test worthiness of wheelchair restraint systems and wheelchairs for commercial and private flight. All Wheels Up conducted the first ever crash test for wheelchair spots. We funded two crash tests one in 2016 and one in 2019—both proved to the FAA that the wheelchair spots were able to withstand 16 G-forces.

We don’t think that there will be one type of wheelchair spot that will work for all airlines or all airplanes. I believe that there are multiple configuration ideas. We live in a world where every organization is full of ideas, and I think all of them should come to the table and all of them should be funded for research.

As for the locking systems, there isn’t a device today that exists that the FAA has said is suitable for air travel. There are multiple companies working on that. But the goal is that there would be a universal locking system, just like in your minivan or on the bus that would be able to tie down any wheelchair. That is the ultimate goal. The goal is for the wheelchair user to use their favorite chair brand per se and not have to use a different brand. We are working with all of the wheelchair manufacturers.

Miller: Can you explain the cure-based non-profit approach?

Erwin: When I was saying we’re set up like a nonprofit cure-based organization, they pay for all the tasks in the pipeline to a cure. There are maybe five tasks to that cure. We’re paying for all of those tasks to be investigated and researched. We don’t necessarily believe that, just like in drugs, that there’s necessarily one solution.

Sorry that my dogs are barking!

Miller: (laughs) That’s OK! They’re excited!

Erwin: They’re as excited as I am, darn it! “Where’s that wheelchair spot?”

Currently, we’re funding university projects for support data, such as, budget impact models, regarding adding a wheelchair spot. Airlines may consider this a cost detriment, but we want to demonstrate that by adding a wheelchair spot you can save money and increase revenues.

We’re all about information-sharing. We have been speaking for over ten years with the regulatory agencies, FAA, the FDA, DOT, RESNA, and other organizations that create these standards. We want and encourage all of these manufacturers to talk to each other. We goal is to get everybody collectively working on accessible air travel; working toward the same goal.

Miller: Were you aware of the PVA’s fight for the airline industry to keep tracking damaged wheelchairs?

Erwin: All Wheels Up works very closely with PVA and we are a part of the PVA informal coalition that works towards accessible air travel. We have a very good working relationship.

Miller: Do you know of Dr. Haseltine’s work on protecting wheelchairs during travel?

Erwin: I am not familiar with Dr. Florence Haseltine personally, but I am aware of the cases. All Wheels Up applauds all work being done to improve accessible air travel. We are working on the long-term goal which is a wheelchair spot that will translate to safer travel for the wheelchair user (both physically and physiologically), as well as reduce the risk of damage of the wheelchair because it will be used as its intended use a transport seat vs luggage.

Miller: Where are you today?

Erwin: We’re funding a strategic roadmap uncovering what actions need to be considered—like, financial impact, safe evacuation plans, and standards for wheelchairs that can be used in the designated spots. We are asking the hard question: how do we get from today, with no wheelchair spot on airplanes, to implementation and certification?

Every organization is considered a stakeholder–whether a plane manufacturer, an original equipment manufacturer who creates the inside of the airplane, to the wheelchair manufacturers and the wheelchair tie-down manufacturers—what is their role? When do they step in? When do they step out? When do they have to all work together? We’re creating that road map because now we have multiple organizations that haven’t necessarily ever worked together before, but are focused on the same goal. We want to create a successful collaboration.

Miller: You’re like a hub.

Erwin: Yes. I definitely would think that we are the project manager of this in large scale, absolutely.

As funders and project managers, we make sure that the ball doesn’t get dropped. We constantly beat that drum to make sure that the work is being done. If we have to fund it ourselves, we will, because we wouldn’t be having this conversation today about a wheelchair spot on airplanes if it wasn’t for the fact that All Wheels Up paid for the first round of testing back in 2016 and then subsequently funded the next round of testing in 2018. Airlines asked a lot of questions and we answered those questions. So basically, that’s what we do. The airlines said, “Great, you’ve proved it’s possible. What will it cost me?” That’s now what we’re coming to the table with.

Miller: How is a wheelchair stored during the flight?

Erwin: Power chairs, and any other heavy wheelchair, are stowed in the cargo part of the aircraft. The DOT requires airlines to return your assistive device in the same condition as it was received. However, that does not always happen. The working number that we’re using, because it’s good data before COVID, is 28 wheelchairs are damaged per day. That’s over 10,000 annually.

Miller: That’s a lot of damaged chairs.

Erwin: At the end of 2018, the government started requiring airlines to report the number of damaged devices. We are funding a paper right now to get what those numbers were prior to 2018. We’re also going to do a forward trajectory of what these numbers could look like in the future if nothing is done. I’m a part of the ACAAA informal working group coalition of large organizations like Paralyzed Veterans of American, which leads that coalition, and others, but something I learned just recently is that while there’s a mandate from the FAA Reauthorization Act for fines, no fines are actually implemented for damages of wheelchairs.

Wheelchairs are frequently damaged; there are cases where chairs have been dropped on the tarmac, and even lost. Disability activist Engracia Figueroa died in October 2021 due to the damage done to her custom chair by the airline. Engracia used a loaner chair that airlines gave her in July while her chair was being repaired. She ended up with sores because of an ill-fitted chair .She died due to the complications from the sores. We already know that there will be a public hearing with the DOT to discuss the damages of wheelchairs.

Miller: That is terrible. People’s chairs are their lifelines; it’s their connection to the world.

Erwin: I think damaging someone’s wheelchair is basically breaking their legs and their hearts. For the sake of argument, let’s say the airlines are fined $700 per damaged chair. I think it should be more, but let’s use it. That’s over $7 million on 10,000 wheelchairs. What we should also be asking is why aren’t the airlines fined? I understand that they’re paying damages to wheelchairs, but why aren’t they being fined? I think we should definitely be asking our Congress people why this hasn’t been implemented.

Miller: How has the pandemic impacted your activities?

Erwin: Back in 2020, when the world shut down, we were told that there was no appetite for accessible air travel. While there wasn’t necessarily “work to be done, we didn’t stop. We worked internally, figured out what we’re going to do.

We launched our Fly Safe Today program. In our initial pilot program, we gave away special needs harnesses for those with reduced upper trunk strength to support them in the seat during air travel. We also gave away ADAPTS evacuation slings that can assist crews transfer special needs passengers in emergency situations. We ran out within 48 hours. We are now funding another hundred sets. We don’t feel that people with disabilities need to fund their own safety, and if the airlines or airplanes or airports aren’t going to provide this, we’re going to try to do that. We’re now providing these for free, all contingent on funding.

We have a deeper waiting list than the hundred, because there is such a need in white space for this program. It would appear that, again, we were the only organization looking to fund research for a wheelchair spot and the only organization looking to fund safe, accessible air travel within the parameters that is it today.

Also we are advocating in Congress for very specific ADAPTS evacuation slings to be added to every emergency kit, of which there are three on any single-aisle airplane, to be added to every plane.

Miller: How are the slings designed to work to help evacuate a disabled person?

Erwin: The slings can be brought on in the passenger’s bag. If there is any emergency, the sling can slide under the passenger. The sling is from the head to below the knees. I think they’re over six foot long. And they have multiple handles on each side. Several people can get that person down in the aisle and onto the sling. The sling can then be lifted by flight attendants or good Samarians, and the passenger can be carried out safely.

This sling has already been used in an emergency situation. We sent this information on this particular evacuation to the FAA, the DOT, and the Senate Transportation Committee. This particular device was used in an emergency landing at Dulles Airport in 2018 with a young man who had cerebral palsy, and he was safely evacuated down the deployed slide. There was smoke in the cabin, and other people with disabilities and elderly were left on board because the crew didn’t know how to get them off of the airplane. The ADAPTS evacuation sling was borrowed from this family because the flight attendants were unprepared. They borrowed this ADAPTS sling from this family to rescue the other people from that airplane. If this is not an example of the airlines being ill-prepared for an emergency when it comes to people with disabilities, I don’t know what is.

Miller: What is Congress doing? What’s the next thing that’s slated for you to talk to Congress about?

Erwin: We have a lot of different projects that we’re working on. The first one is the ACAAA, the Air Carriers Amendment Access Act. That is an updated version of the ACAA, which is the Air Carriers Access Act. Different wording is being added that specifically to make airplanes more accessible. We tried to get an expanding wording in there than just the very broad stroke of makes planes “accessible.” We wanted to specifically have a wheelchair spot added to that. We were unsuccessful. However, we think maybe in the 2023 FAA Reauthorization Act, we push a little harder and maybe see where we can get there and ask for maybe funding for the OEM to invest specifically into that.

Erwin: There are so many things that we need to investigate. I’d like to see the reporting of how many disabled people are injured whether it is from the transfers from the wheelchair to the airplane seat or sustained injuries because of not having their wheelchair. I’d like to see some of these numbers. Just like we’re really surprised with the number of damages of wheelchairs, I think we’d be really surprised. I have been told that Engracia Figueroa’s death is not the first one; it’s just the first one that’s been reported.

We need to make sure injuries, meaning pressure sores or anything like that, are also documented. If this is happening, we should see if we can get the airlines to pay for medical services in addition to wheelchair repair damages.

Miller: So this kind of comes full circle–back to the wheelchair itself. Don’t airlines have guidelines on how to stow wheelchairs?

Erwin: There is work being done by a lot of organizations, the airlines, the wheelchair manufacturers trying to figure out what the best way is to handle wheelchairs and have them be stowed. At the end of the day there is no best way.

For example, we can say, the best way for a 400-pound wheelchair is to have a lift and the lift from the ground up into the conveyer belt and in. Even if one airport has one lift, it’s not getting to the gates that are in need of it. If there are over 40 gates at an airport, you need more than one lift.

Miller: Would this fall under a safety violation by damaging the wheelchair?

Erwin: I don’t know if this is necessarily a safety issue in respect to the damage to the wheelchair. But I would say that probably a safety violation is that airlines are the only organizations that get to sidestep OSHA. If you read OSHA regulations, employees can’t lift over 50 pounds, and especially not in a twisting motion. You are required to use special devices. Airline crews are lifting disabled people into an airplane seat, and on top of that, they’re doing that lift into twisting motion in a very small, very restricted area. And then you have four people lifting a 400-pound wheelchair, that’s still 100 pounds, 50 pounds over OSHA’s regulations.

Again, the airlines and the airports are the only organizations that are not fined by OSHA in regards to not meeting these safety regulations. To me, it’s always the why. Why? Everybody keeps saying that the airlines are so big, things like that. To me, that’s an interesting—when I learned that, that’s interesting to me, that there are no fines there, either.

In our budget impact model, we’re also showing how many airline staff are out on disability whether it’s the lifts of the wheelchair or the lifts of the people getting into the airplane seat and how many people are out on medical disability. However, why aren’t there fines also being incurred by these organizations for putting these people at risk?

Miller: Really, it’s a very complex problem!

Erwin: Quite, quite, yes. The airline industry that says they’re all about standards and the rules, but they don’t seem to follow the rules when it suits them. That is what amazes me is, they’re all about the red tape, but they can easily skirt any of the rules when it benefits them.

Miller: Are the airlines losing potential customers from disabled community?

Erwin: One hundred percent. We know about 40% or more of disabled people do not travel. If you think of one person who uses a wheelchair who won’t travel, they typically don’t travel alone. If you say 40% or more people aren’t traveling, think of that one ticket and times it by four because that one person is traveling with a significant other or an aide or their entire family. If they could have the opportunity to fly, instead of driving to that destination, they would fly to that destination.

Miller: Right. And definitely it’s not all for pleasure. I’m sure it’s for medical care and medical assistance, research, test trials, things like that.

Erwin: Absolutely. We are communicating and trying to work with the pharmaceutical companies and talk about our work and say, “We’re here for you. You’ll get access to clinical trials, access to your medicine, access to care.” We’re definitely beating that drum as well. It’s a multifaceted problem, and when you start unraveling this very large onion, and it has so many layers, it’s not even access to care, what about fair and equitable employment. We know people who have to take their own vacation time to drive to conferences, to business trips because air travel is not accessible. Why are they expected to take their own private vacation time to drive because they need to be at peer-related events?

If large employers, say the Fortune 1000 companies are saying that they want equitable employment for people with disabilities, and then this should also be on their platform, making sure that accessible travel is there for their employees.

We’re working on a new bill to create special funding specifically for accessible air travel, so OEM can get that special money. Whatever we’re working on, you can keep informed if you follow us on social media.

Miller: What does your son say about you and all your energy for him and his future?

Erwin: He’s 14 now. I started this 10 years ago. He loves it. I don’t think he knows a life without it. He’s used to Mom traveling for this all the time. He knows I go to Washington DC a lot or other places around the country and the world to talk about accessible air travel. I think he’s proud of me.