ARTICLE FROM ABILITY MAGAZINE: (Cica 1999)

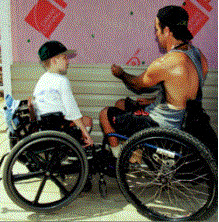

ABILITY Magazine is partnering with Habitat for Humanity to build homes for people with disabilities of low income. What is really unique about this project, and a historic first, is that volunteers with disabilities will be building the homes. Volunteers will have a full range of disabilities including physical, learning and mental disabilities. The reason is to demonstrate that much too often people with disabilities are overlooked as a valuable resource for employment and volunteering. “We are all connected. Who doesn’t want their community to flourish?” says Millard Fuller, Habitat for Humanity’s founder. Yet an often underutilized resource of community participation may be the talents and skills of people with disabilities as mentors and volunteers. The sense of “community” hits home when we think of how many of our lives have been affected in some way by our association with relatives, friends, neighbors, or co-workers experiencing a physical or mental disability. The reality is that about half the nation is touched either directly or indirectly by disabilities. Additionally, studies show that during an average lifespan Americans can expect to have one or more disability for approximately 13 years. Perhaps those statistics seem surprising, until we think of numerous different types of disabilities. Most disabilities are hidden such as: hearing loss, diabetes, heart and lung conditions, mental disorders, learning disabilities, and the sequelae of more pervasive conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis or other neurological illnesses, or HIV/AIDS.

The first build of the partnership between ABILITY Magazine and Habitat for Humanity – May 30, 1999 through June 4, 1999 is in Birmingham, Alabama. What will power the building, is the compassionate drive of the human spirit to help its fellow man-and what a drive that is! Chris Wright is the proud recipient, as well as one of the proud builders of his new home. Chris is a paraplegic who lost use of his legs at age 29 from traverse myelitis; an infection of the spinal cord. As with other volunteers, he has meet the requirements for Habitat and provided 300 hours of volunteer service.

Habitat for Humanity International was founded in 1976 by Millard and Linda Fuller. It is a nonprofit, Christian housing ministry dedicated to eliminating substandard housing and homelessness worldwide. Habitat for Humanity makes adequate, affordable shelter a matter of conscience and action. Habitat invites people from all faiths, and walks of life to work together in partnership, building houses with families in need. Habitat for Humanity was borne out of a personal transformation experienced by Millard Fuller. At age 30, Fuller was living the American dream. He was a self-made millionaire with a drive to make more and more money. But his health and marriage were compromised. When Fuller’s wife threatened to leave him, he began to turn inward to question what was really important to him. What ensued was a reconciliation in his marriage and a renewal of his commitment to Christianity. The Fullers then took a drastic step – they decided to get rid of their accumulated wealth and start over.

The Fullers ended up at Koinonia Farm, a Christian community located near Americus, Georgia, where people were looking for practical ways to apply Christ’s teachings. They initiated several partnership enterprises with Clarence Jordan, a radical Christian leader. Jordan supported the avenue Fuller had decided to take in his life. One of the Koinonia Farm enterprises which became successful was a ministry in housing. The model that developed became the basis for the Habitat idea. Modest homes were built on a no-profit, no-interest basis, thus making homes affordable to families with low incomes. Each homeowner family was expected to invest their own labor into the building of their home and the homes of other families. This reduced the cost of the house, increased the pride of ownership and fostered the development of positive relationships. Money for building and from house payments was placed into a revolving fund and used to build other houses.

In 1973, Fuller and his family moved to Africa and began to test the model outside of the United States. The housing project they built in Zaire became a successful housing project for the developing nation. Fuller became convinced that this model could be expanded and applied all over the world. Upon his return home in 1976, he met with a group of close associates who were involved in the work. They decided to create a new independent organization: Habitat for Humanity International. Since then, the Fullers have devoted their energies to the expansion of Habitat throughout the world. Fuller sees life as both a “gift” and a “responsibility”. “My responsibility is to use what God has given me to help His people in need.”

Today, Habitat for Humanity is extremely successful, perhaps because it makes a simple human need – decent affordable shelter, a tangible goal. Millard Fuller, points out that one basic human need, “to have a decent place to sleep…” is one “that will elicit almost universal acceptance.” Volunteers who participate in Habitat builds are rich, poor, young, old, of all religious persuasions, all races, and cross political lines. Fuller also points out that Habitat for Humanity provides a “hand-up” and not a “hand-out for recipient families.” Former President Jimmy Carter says “Habitat substitutes the idea of partnership for the stigma of charity.” The recipient families work side by side with the volunteers to create the home. The idea of recipient families investing their own labor into their house and other Habitat houses is called “sweat equity”. Fuller describes sweat equity as follows: “Sweat equity reduces the monetary cost of the house, increases the personal stake of the family members in their house, and fosters the development of partnerships with other people in the community. The amount and type of sweat equity required of each partner family vary…300 to 500 hours per family is common.” Over the years, Fuller has noticed how the elimination of poverty, substandard housing and homelessness in recipient families creates a transformation “on the inside” of family members – dignity and hope replacing hopelessness. For recipient children, Fuller has noticed dramatic changes – children who used to do poorly in school become better students from having a place to study, and a roof over their head.

Habitat has built some 70,000 houses around the world, providing more than 350,000 people with safe, decent, affordable shelter. Through volunteer labor and tax-deductible donations of money and materials, Habitat builds and rehabilitates simple, decent houses with the help of the homeowner (partner) families. Habitat houses are sold to partner families at no profit, financed with affordable no-interest loans. The homeowner’s monthly mortgage payments are recycled into a revolving Fund for Humanity that is used to build more houses. Currently, a three-bedroom Habitat house in the United States costs the homeowner an average of $42,500. Prices will differ slightly depending on location and the costs of land, professional labor, and materials. Houses have been built worldwide. Families in need who would like to be considered for a home apply to local Habitat chapters called “affiliates.” The affiliate’s family selection committee considers an applicant’s level of need, willingness to become partners in the Habitat program, and ability to repay the no-interest loan. Every affiliate follows a nondiscriminatory policy of family selection. Neither race nor religion is a factor in choosing Habitat homeowner families.

Two of Habitat’s most famous and hard-working volunteers are former President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn. The Carters had been involved with Habitat in a peripheral way – by donating money, by speaking at engagements, and launching the first “Habitat Walk” to raise funds. Fuller had wondered if the Carters would become more involved with Habitat, and he asked for a meeting with the former President Carter. Fuller says that this was in keeping with Fuller’s own philosophy of “asking” rather than “not asking” – having learned that more happens when one asks.

On meeting with the Carters, Fuller was direct: “Are you interested in Habitat for Humanity or are you very interested?” he asked. President Carter smiled broadly, looked at Rosalynn and then quietly replied: “We are very interested.” “Well,” Fuller responded, “what do we do with that interest?” “Write me a letter” Carter suggested, “outlining ideas you have on how we might be involved. And don’t be bashful.” Since then, the Carters have helped immeasurably raising funds and volunteer interest, publicizing Habitat’s good work, visiting overseas projects, and helping with the builds. Each year since 1984, Jimmy Carter donates his time especially during what has become known as the “Jimmy Carter Work Project.” Fuller says, “The media loves what Jimmy Carter is doing. A former president spending his time, not in luxury in some heavily-guarded and plus enclave, not at fancy hotels and jet-set parties, but building houses for and with people who need them.”

Other productive groups and celebrities have been highlighted in the media for their participation as volunteers and spokespeople for Habitat. What seems tantamount is that the volunteers feel greatly enriched in giving of themselves in this way. The famous folk giving their time and energy to Habitat have included Singer Amy Grant, Bob Hope, Paul Newman, Country Singer Rebe McEntire, Author and Humorist Garrison Keillor, World Heavy Weight Boxing Champion Evander Holyfield, Football Players as John Ellway, and the list goes on and on. Proving that the desire to lend a helping hand to Habitat is bipartisan, volunteers have also included Bill and Hillary Clinton, Al and Tipper Gore, Former

Congressman and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Jack Kemp, as well as Newt Gingrich. Habitat’s volunteers have also included groups organized with certain themes in mind. There have been student groups, women’s groups, groups that travel in R.V’s from site to site (Habitat’s “R.V. Care-a-Vanners”), more formal groups such as First Ladies for Habitat, and many, many others. What has been proven in Habitat’s history is that Habitat’s collective spirit of helping is contagious. Millard Fuller’s speaking engagement calendar is full of worldwide engagements yearly, and future builds planned in Habitat are ongoing. In addition, Fuller has written several books: No More Shacks, The Excitement in Building, The Theology of the Hammer, A Simple, Decent Place to Live. ABILITY Magazine welcomes the partnership with Habitat for Humanity and embraces the genesis of future efforts to make housing more accessible to people with disabilities with low-incomes.

Volunteer Gallery – a work in progress

First US Invitation – China’s International Integrated Art Exhibition