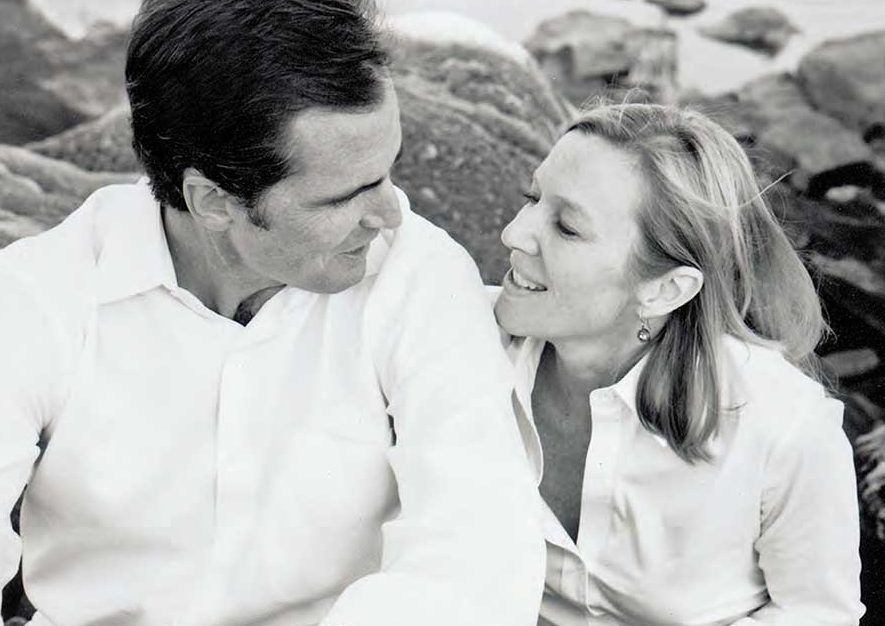

Circa 2007

As he traveled through Iraq with a U.S. military unit early last year, World News Tonight co-anchor Bob Woodruff was severely wounded by an insurgents’ improvised explosive device. His new book, In An Instant, chronicles that experience. Both he and wife, Lee, his co-author, contribute journal entries about the 36 days he spent in a coma, the impact of his brain injury on their family and their combined efforts to help a broken newsman heal.

BOB

TAJI, IRAQ, JANUARY 28, 2006

We hit the ground running in Baghdad and put together what would turn out to be my last news piece for over a year. It was a story about a Baghdad ice cream shop, of all things, a slice of real life in the midst of a chaotic and violent city. With many news stories about the horrors of war, there is no real context for Americans to get a sense of what daily life is like for the Iraqis, and we wanted to find a way to convey that. This little ice cream shop was an oasis in a land pockmarked by war. It was a simple story, an example of how life goes on. Over time, the shop had had some close calls; car bombs had exploded mere blocks away. But in the evening, Iraqi families gathered there with their kids and shared an ice cream, and for that brief moment they could try to forget that they were standing in the middle of the worst war zone the world had seen in a long time. It was an unexpected story of resilience amid a terrible backdrop.

Later that night, Vinnie Malhotra, our producer, Doug Vogt, our cameraman; Magnus Macedo, our soundman, and I prepared for our trip with the military the next morning. We each grabbed body armor from a pile on the floor of the Baghdad office. Doug had his own helmet and flak jacket that he carried into every war zone. I grabbed a helmet and flak jacket with a neck guard. Somehow, the next day, too tired to think much about it, I would end up with a different jacket, the one with no neck guard.

BOB

TAJI, IRAQ, JANUARY 29, 2006

We packed our gear in an SUV and drove to the mess hall. We were in great spirits. We had gotten some terrific interviews from the soldiers and we’d gained a greater understanding of what was happening on the ground on the eve of the president’s State of the Union speech, where we knew he would address the issue of training Iraqi troops for an ultimate handover at this critical juncture of the war.

Over breakfast we talked about how much footage we already had and how we probably didn’t really need to do this final part of the embed. But we had pushed hard for access to the military, and the Fourth Infantry Division had been gracious enough to set up this opportunity for us on short notice. It would have been rude, we thought, to have canceled on this last leg.

That morning the military wanted to take us to an Iraqi water-treatment plant, which provided fresh water for the town. Insurgents had attacked the facility while it was under U.S. protection and now it was in the hands of the Iraqi soldiers, who were doing a good job of securing it. A huge hole had been blasted through the center of the plant by a rocket-propelled grenade and the station grounds were muddy.

“Man, I hate driving over this sh#*. You never know what’s underneath there,” the driver of our Humvee muttered under his breath. We knew he meant improvised explosive devices or IEDs. The insurgents had been clever about placing these bombs, and the number of IED blasts had ratcheted up in the past few months. The men had good reason to be jittery. I was too.

All told, we had traveled only three miles or so when there was a giant explosion, a deafening, horrific blast that rocked the tank. Hidden behind some trees, a band of Iraqi insurgents had detonated a crude roadside bomb with a remote-controlled device. The IED was a 155- millimeter shell, one of the biggest artillery shells available. This was a well-planned complex attack. The bomb was set off to the left of the roadway, about three to five yards from the tank.

Hundreds of rocks and stones, which had been packed around the shell in the dirt to magnify the damage, shot upward with the force of bullets. The explosion blew up and under the tank, powerfully showering the side of the vehicle, the angle of the blast effectively saving our lives as most of the shrapnel flew over our heads.

I took a direct hit to the left side of my head and upper body. More than a hundred little rocks and countless fragments of black dirt were blasted into my face, peppered around my eyes, tattooed onto the bridge of my nose and ear, and shot into my jaw and under the helmet. One marble-sized rock sheared off the bottom of my jawbone, cracked two teeth, and entered the soft flesh of my neck. A second marble-sized rock ripped into my cheek and up into my sinus, coming to rest up against the eggshell-thin bone of the eye socket. Another rock tore into the chin strap of my helmet, blowing it off my head and into the sand several yards away. The force of the blast was so strong that it crushed my skull bone over the left temporal lobe of my brain. Small shards of my cranium were driven into the outer surface of my brain, and the force was so great that my left eyeball was slightly displaced in the socket.

Three large rocks and dozens of smaller ones shot under my flak jacket in the back by the armhole, slicing into the flesh and cartilage of my scapula like tiny, dulled knives, coming to rest just a millimeter from my chest wall, heart, and lungs.

Doug was still filming as his skull absorbed the concussive blast from the front, but his helmet stayed on. The force of a giant rock slamming into his helmet shattered his skull. Only a few rocks hit Doug, though, as the force of the blast slammed him onto the top of the tank on his back. In shock from the concussion, he could not move and lay staring up at the blue cloudless sky. The Iraqi soldier riding at the front of the tank had one of his hands blown off.

Below the hatch, Magnus had been holding Doug’s legs as he filmed. The blast caused Magnus to fall back and lose his grip. Vinnie and Magnus looked at each other for a split second and screamed. Doug’s camera fell down into the hatch and instantly Vinnie looked up and saw my body sway and crumple down into the tank in a kind of macabre slow motion, blood streaming down my face. As I fell into the vehicle, my helmetless head and the back of my neck ricocheted off the hard metal on the sides of the hatch like a child’s rubber ball. For more than a month I would be completely unaware of anything that was happening around me. My mind would journey to a place that to this day I cannot describe or even remember.

LEE

WESTCHESTER COUNTY, NEW YORK, JANUARY 23, 2006

What would you do if someone told you that the next moment would be the last time you would hold or hug or converse with your husband for over a month, that he would lie for five weeks in a comatose state, clinging to life? How would you act if you knew your husband would spend the next year and beyond recovering from a traumatic brain injury, dealt by a roadside bomb powerful enough to blow open his skull? What would I have changed about that moment, that morning, if I had known my family would be torched by a wartime explosion?

LEE

BETHESDA NAVAL HOSPITAL, MARCH 9, 2006

Driving to the hospital on the morning of the third day after Bob’s awakening, my cell phone rang. It was an unfamiliar area code, and out of curiosity and given the early hour, I answered it.

“Hi, there,” said a man’s voice.

“Hi,” I said, tentatively. My new life had made me wary of almost everyone. “Who is this?”

“It’s Bob.” He sounded ticked off that I hadn’t recognized his voice. “Oh, sweetie!” I said, with a mix of incredulity and relief. “I—uh, I just didn’t expect you to call me. It’s been so long since I picked up the phone and it was you.” “Well, I hope I’m not bothering you,” he said, annoyed, completely missing the importance of the moment.

“Where are you? When are you coming?”

“I’m on my way,” I told him. “I’ll be there in four minutes.”

“Well, I was just looking for the…well, I’m trying to cut . . .” and then he trailed off, unable to think of the word. The amazing thing was that I knew he was looking for nail clippers. I could understand how his mind was working as he sputtered out words that sounded roughly like toe, walk, and foot.

“Are you looking for the nail clippers?” I asked patiently, in a shockingly mommy-ish voice. I could see this new job was going to require a different kind of patience, as had pushing Nora’s hearing aids back in her ears, over and over again, when she was first diagnosed with hearing loss. His need was sobering.

“Yes,” he said, relieved. “Nob… shooters. Where are they?”

When I walked into the hospital a few minutes later, the doctors told me Bob was running laps around the hall. “What?” I said. I looked up and there was Bob, in his goofy white plastic climbing helmet and with a nurse by his side, slowly jogging and simulating lacrosse moves, unaided, down the long corridor. When he finally saw me, he immediately stopped and stood, showing off and put one foot on the inside of his other leg with his palms touching in front of his face, balancing in a yoga-tree pose.

“Hey,” I said slowly, already hating the white plastic helmet that we would be living with, possibly for months, until they replaced the skull bone.

“Sweetie!” he said, and he put his arms out and began to run toward me in his too-short T-shirt and cutoff hospital pants like a man with a new lease on life in one of those horrible erectile dysfunction ads. The entire nursing floor and the doctors doing rounds all laughed as we hugged in an over-exaggerated, B-movie clinch.

“Let’s take it in the bedroom,” I joked to our makeshift audience.

With every brain injury there is always payback for the great days and the surges of energy where the patient pushes it. Especially early on, one day of feeling great and the resulting frenetic activity means the next day will probably feel like a setback. So it was for Bob the following morning. He was tired and nauseated, but miraculously his speech continued to return.

During one of his first cognitive tests, the reality of what Bob had lost was driven home to me. The neurologist held up cards with pictures of objects, and as I watched I realized that Bob could not come up with the words for bird or tree. For broom, for example, he would say, “It sweeps stuff on the floor.” But despite the elementary nature of the tests, the neurologist, Dr. Degraba, was obviously pleased.

He asked Bob to copy two intersecting pentagons, and Bob did this almost perfectly. Then he scribbled something inside each of the pentagons. One held the word love, and in the other pentagon he’d written tempest. Dr. Degraba studied Bob’s scribble for a bit and seemed to dismiss it. “I’m not sure what this is all about,” he said, showing me the words when he reviewed Bob’s results.

I knew instantly. Those pentagons represented the two halves of his brain. One contained the love he felt for his family and the gratitude he had for being alive; the other side was the tempest, the horrible raging fear and disorientation that lived in his brain right now, as he tried to make sense of his new world.

“It would have been better for you if I had died,” he said to me, later that day. “I am so sorry.” I tried hard to buoy his spirits. Bob was keenly aware of his deficits, an uncommon quality in most newly brain-injured patients. Like so many things about Bob, his self-awareness was remarkably intact. Most of the time his sense of humor was in evidence, but I knew he was using it like a mask. When that mask slipped, on those rare occasions where he was sad or just plain exhausted, he would allow himself to feel the fear and terror of what had happened to him and what he did not remember.

LEE

WESTCHESTER COUNTY, NEW YORK, MARCH 19, 2006

Bob was in capable new hands at the rehab facility in New York City, and he was now only a 40-minute car ride from our home. We had made the transition. Another change, one of so many.

Dr. Costantino and Dr. Sen came by to see Bob in his new hospital room at Columbia-Presbyterian the next morning. They began to talk to us about the next surgery, the big one. This would be the cranioplasty operation to replace Bob’s skull, and they had decided on May 19. Bob’s spirits fell. Another nine weeks of living with the hated helmet and with pain and disorientation. But they had to be sure Bob was well past the risk of any infection from the pieces of dirt and rock shrapnel that had been embedded in his scalp.

At that time the surgeons would do some more work on smoothing the jagged scars on Bob’s face. They would try to make his tracheotomy scar look better and remove the many dozens of tiny rocks that still peppered the left side of his face. Although the surgery would take place in New York, Dr. Rocco Armonda from Bethesda Naval would be there as well. Once again, it would be the dream team in the operating room. The presence of these men would make me feel calm and in capable hands.

The army’s Walter Reed Hospital had already created a state-of-the-art model of Bob’s new acrylic skull plate from high-tech 3-D CT scans. A specially created bone epoxy, developed by Dr. Costantino, would fill in the seams where remaining skull met acrylic. The combination of these two procedures was brandnew. After Bob’s “joint venture” surgery, future military cranioplasties at Bethesda Naval Hospital would use this method.

The ophthalmologist in Bethesda, and later in New York, was amazed at how Bob’s left eye had been spared. It was another miracle. Small rocks were scattered all around the eye socket and in the upper and lower eyelids, but nothing had hit the eyeball itself, even though he hadn’t been wearing blast glasses. Later, Bob would joke that he had his deep-set eyes to thank; they receded so far in his head, the eyeball had been spared.

Now that Bob was awake we could also deal with the issue of his hearing. The audiologist found, amazingly, that he had lost only about twenty decibels. “Most of his hearing is there,” the doctor told me. The IED had exploded just feet from Bob in a flash of white light with what must have been the sound of an apocalypse. I remembered first seeing his ear, bloody and mangled, like a piece of pink cauliflower oozing fluid; surely, I’d thought, Bob would be deaf in his left ear at least. The doctor explained that there was a hole in the tympanic membrane; if it did not heal on its own, he would sew it up during the cranioplasty.

After just three weeks, Bob had cycled through the inpatient phase of his recovery and was ready to come home. I was terrified. The medications, the constant fear he might fall and hit his head—these concerns had all been in the hands of nurses until this moment. Now Bob was going to be my responsibility. It felt like carrying an egg on a spoon.

BOB

COLUMBIA-PRESBYTERIAN MEDICAL CENTER, NEW YORK, MARCH 2006

Although I was still in pain and would often have to lean against walls and door frames for balance, there was a definite shift in my abilities. The biggest difference was that the constant pain was receding. In the beginning, at Bethesda, I had been able to sleep for only an hour or two at a time. Part of that was the initial excitement of being alive. I was thinking about so many things. But much of my discomfort was due to the ongoing pain in my head and back. It was hard to focus. Although I was often hard on myself and on the slow pace of my progress, I could see small changes. More words were coming, though I tired so easily it felt like failure sometimes.

I had occupational, physical, speech and recreational therapy almost every day, and by dinner I found myself exhausted. Often I would have to nap to get through the day.

Initially, Lee had accompanied me to some of my sessions, but increasingly I didn’t want her to see the plain truth of how little I could do. I was missing so many words. While I was learning to get around this in conversation, or rely on others to fill in the blanks, there was no going around things in therapy. As much as I loved and respected my therapists, they were not there to give me a break. It was their job to help me put it all back together, to teach me coping skills for my deficits. In the early days, the grueling nature of these sessions was like a cold shower. The therapists kept telling me that all the words were in my head somewhere; it was a matter of building the new neural connections that led to them. Much of it was time. The brain takes longer to heal than any other organ.

I watched Lee’s face once while I was fumbling for the word lettuce in the therapy room. She looked scared and very small. She was exhausted and she had lost too much weight. Her broad swimmer’s shoulders hunched forward. I remember feeling how much I wanted to make this all right with her. Just then, I wanted so badly to come up with the word lettuce and I couldn’t. I was using every bit of energy I had to get through my own days. Just one day on the rehab floor in the hospital felt like a whole week in what had been my former life.

LEE

ST. LUKE’S-ROOSEVELT HOSPITAL CENTER, NEW YORK, MAY 19, 2006

After so many agonizing days, hour after hour of waiting and worrying, of watching Bob weak and in pain, the date for the cranioplasty surgery had finally arrived.

Bob was nervous. This was the first surgery that he would be aware of after his injuries, and the thought of someone carving his head like a pumpkin made him incredibly anxious.

More than four hours later, the surgery was a success. Dr. Costantino and Dr. Armonda had shaved the acrylic skull plate a little to make it more symmetrical and then molded the soft hydroxyapatite cement into the edges. It would fuse to the bone like real bone, filling in the ridges around the skull plate. It had taken a few tries to render it the way they wanted, but like a pair of Renaissance sculptors they were pleased with the symmetry that resulted. In the recovery room, Bob’s head was covered in bandages with a drain coming out, to collect the liquid draining off his scalp.

After almost four months, Bob finally had a rounded head again. There would be one more operation later to fill in the left temple where the muscle was shattered and then reattached, but the doctors needed to wait to make sure he was past the risk of infection. Some of the black spots we had thought were rock turned out to be dirt, blasted into the skin around his cheek, nose, and eyes. It would be impossible to take these spots out surgically and they might never rise to the surface to expel themselves. This was of no concern to Bob. He refused any future surgeries just for aesthetics. “I’ve earned these scars,” he would joke.

BOB

WESTCHESTER COUNTY, NEW YORK, MAY 27, 2006

It was the heart of Memorial Day weekend, and the drain and tight bandages had just come off. I’d had a rough recovery from the surgery and there was a great deal of fluid building up under my scalp, which was uncomfortable and scared me. I hated the dreaded bandages; it took all the self-restraint that I had not to claw them off at night. Dr. Costantino explained that they were wound so tightly around my head to counter the fluid build up from the operation. But it felt like a cruel turban, and I was tired of the pain.

Day by day, week by week, I crawled out of this phase of recovery and began to feel better. With my new head and no more helmet, I felt like a man let out of prison. I’d had daydreams of crushing the helmet with my car or smashing it with a hammer, but once the surgery was over I didn’t feel any anger or need for release. The helmet ended up in the basement as what I hoped would be a relic of this time in our lives.

BOB

DECEMBER 2006

With the help of intense cognitive rehabilitation, the healing powers of the human body, and the profound support of friends and family, I have come closer to my old self, little by little. But I will never be the same. No one can undergo a life-changing event and be the exact person they were before it happened. I am a more grateful person now, on so many levels. I truly appreciate the depth of friendships and I’m thankful to have had this time to be more of a presence in my children’s lives.

I’ve also had to relearn how to do certain things I once took for granted. A big part of recovering from a brain injury is to adopt different ways of doing the same thing—“coping strategies” to attack the same problem in a new way. I write down far more things than I used to, I’m better at keeping a schedule, and I’m learning my limits when it comes to fatigue.

After I woke up from my comalike state, I would search for a word or memory, and it would evaporate before me. When I tried to read, I could barely keep a sentence in my head. By the time I got to the fifth word, I couldn’t remember the first three. Now I am able to read faster, write better, remember and process information more quickly than I could have imagined in March.

As I began to think more clearly, I understood that my brain worked in slightly different ways. The only way I can describe this process is like seeing the top of a mountain from a path but without the ability to find the way up. I can still see the top, but I’ve forgotten the exact way. I may not always remember precisely where the path is but by taking one step at a time, little by little, I realize I can still get there, even if I sometimes take a slightly different route. I find the word, locate the answer, and formulate the question as my brain heals, rewires and reconnects.

My vision and hearing were affected in the blast. It’s much harder for me to hear conversations when there is background noise—at a restaurant, for example, or in a crowded room. And the blast, or the fall afterward, damaged a nerve that has left me with a black pie-shaped wedge in my field of vision. I can no longer see objects in the upper right quadrant of my sight. So again, I’ve learned to compensate. I move my eyes and head around more to see. I turn the newspaper at an angle to view it all. But I am no longer very effective at the net in tennis and basketball is out. I have no problem driving, but I miss weekend soccer with the old-guy league in my town. Those sports run the risk of potential damage that a person with a head injury cannot afford.

On June 13, 2006, I returned to the ABC newsroom for the first time since my injury, accompanied by Lee, David Westin, and Charlie Gibson. It was just a month after the surgeons had given me a new skull. My hair was still shaved close to my head, my scars visible. I was tentative at first and then I felt the wave of love and good wishes of my colleagues. I was overwhelmed. There were tears and hugs and stories shared of the places we’d been together, the hours logged in the edit room, the time spent gathering news. I’d missed all of these people and it was clear they’d missed me too. It felt like coming home.

This excerpt was adapted from In An Instant by Bob and Lee Woodruff, © 2007 and published by Random House.