We are building a new way to make connections

for performers with disABILITIES in the Entertainment Industry

If you are an Actor, Musician, Speaker or Comedian

click on abilityE to receive an invitation to post your profile during our pre-launch phase

How far have we come? (ABILITY Magazine circa 2009)

Like a lot of children of the ‘80s and ‘90s, I spent a lot of time in front of a television in my formative years. Somewhere in my mother’s house are stacks of videotapes of Looney Tunes, Seinfeld and Quantum Leap episodes that I watched again and again until their images started to fade. And I’m pretty sure I was the only ten-year-old on my block to dress as Lieutenant Columbo for Halloween.

But in all of my boob-tube-watching childhood, I rarely, if ever, saw anyone like me on television: someone with a physical disability. While I may have subconsciously measured my young self-image against the Kevin Arnolds and the Theo Huxtables (and yes, even the Steve Urkels) that I saw on screen, I knew intuitively that those guys weren’t exactly living life quite the way I was living it. They stressed about acne and homework, sure, but they didn’t have the unique concerns or self-doubts of an adolescent with a noticeable physical limitation. They didn’t use crutches or a wheelchair every day.

Thankfully, visibility for most minority groups has dramatically elevated since the early years of my childhood. Entire networks are now ostensibly constructed around advancement of minority images in television. Celebrities like Bernie Mac, Ellen DeGeneres, George Lopez and others have brought their unique voices and perspectives—and, by extension, more diverse audiences—to the television marketplace. And yet, it’s still a very rare occasion when I see someone like myself in narrative media. Try to name five characters or personalities with a disability on television today and you’ll recognize we remain the minority that even most diversity-oriented programming tends to overlook.

So it was with something of a personal curiosity and excitement that I attended the 2009 Hollywood Disabilities Forum, held in October at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. As a graduate of the UCLA screenwriting program, and as a writer with a physical disability, I am aware that events like this one will prove vital not only in respect to my own career, but also in helping to shape the self-image and social perception of the new generation of children with disabilities—children who, just as I did, continue to search for genuine reflections of themselves in a media that still doesn’t truly see them.

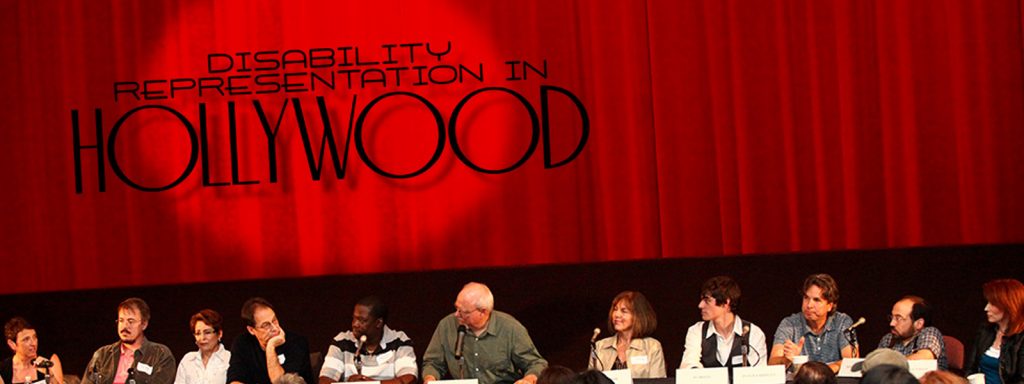

The forum, moderated by author Allen Rucker, boasted an impressive panel of industry talent including David Milch (creator of Deadwood and NYPD Blue), Daryll “Chill” Mitchell (star of FOX’s Brothers), and Margaret Nagle (writer of HBO’s Warm Springs), among others. Discussion topics ranged from the nature of the creative process to the numerous challenges of breaking into the film and television industry with a physical disability.

Actor Robert David Hall, best known for his recurring role on CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, served as master of ceremonies for the event, emphasizing inclusion, accuracy, and access for characters and performers with disabilities. “We’re looking for our opportunities to be seen and heard,” Hall said. “To be cut out of mainstream TV, movies and advertising stinks, and we’re trying to change that.” Hall, who serves as the national chair of the Performers with Disabilities Tri-Union committee, walks on two prosthetic limbs as the result of a car accident in 1978. “It’s crucial for all of us—actors, writers, directors, producers, casting associates—to come together to create solutions. They won’t happen without us.”

But arriving at solutions is difficult when the nature of a problem is still not fully understood or acknowledged. Even as an avid television viewer with cerebral palsy, I was surprised to learn that although 20 percent of people in America have a disability, only one-half of one percent of words spoken on television are spoken by a person with a disability. According to the forum’s keynote speaker Peter Farrelly, this imbalance between representation and reality is self-sustaining, as the lack of people with disabilities in our omnipresent media culture keeps that demographic “pretty much invisible” to storytellers, casting directors, and other industry professionals.

“Unless a role is designated as being somebody with a disability, the truth is, casting is just not seeing you,” Farrelly said. “No screenplay says ‘Amanda, the girlfriend, walks in the room and has perfect hearing,’ but that’s who they’re thinking of when they’re putting the movie together because that’s what they’ve seen before.”

Farrelly—who, with his brother Bobby, created hit comedies There’s Something About Mary, Shallow Hal and Stuck on You—has included people with disabilities in the majority of his films, in hopes of changing what has become normalized in global media. “It’s going to be a gradual change,” Farrelly said, likening the social bias against people with disabilities to that against women in traditionally male professions. “My mother was a great nurse who should’ve been a doctor. Today she’d be a doctor. Progress happens.”

But some members of the panel expressed concern that the very progress they’re hungry for is too often impeded by the casting of able-bodied actors to play characters with disabilities. Television writer-producer Janis Hirsch, who works closely with Mitchell on Brothers, argued that roles for characters with disabilities should be played by actors with disabilities because there is no shortage of available talent in the audition pool. Hirsch cited a recent episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm as representative of what is often a hurdle for the advancement of actors with disabilities.

“The episode had two characters in wheelchairs, played by women without disabilities,” Hirsch said. “I’m sure they’re lovely women, but they’re dead to me. It’s not like there weren’t other talented options out there.”

Milch, whose HBO series Deadwood featured a woman with cerebral palsy in a 19th-century South Dakota brothel, countered Hirsch’s stance by questioning its exclusivity. “I’m not interested in blackballing actors,” Milch said. “It’s a dangerous position to take. I’m not going to hire to meet a quota. Let’s focus on making more opportunities, not fewer, here.”

The collision of these two perspectives sparked thoughtful debate at the forum, drawing feedback from audience members and panelists alike. One actress in attendance expressed that film and television “didn’t need any more Daniel Day-Lewises,” referencing the actor’s Oscar-winning turn as Christy Brown in My Left Foot. Actor RJ Mitte, who holds a supporting role on the popular series Breaking Bad, found a measured middle ground, offering that “the perfect role is out there for everybody, it’s just important to be ready when it comes.”

Though debates like these provide no easy answers, simply attending this event proved to be an eye-opener for me. I left the forum infused with hope and a new sense of perspective, recognizing that perhaps elevating representation of characters with disabilities truly is a social cause akin to those of so many other minority groups of previous years. As a writer, media junkie, and hopeful participant in the future of the film and television, I was gratified to witness so many people of intellect and passion discussing something I had grown up only subconsciously recognizing: if we don’t work to get ourselves reflected in the media, who will...

From the pages of ABILITY Magazine

Volunteer Gallery - a work in progress

First US Invitation – China's International Integrated Art Exhibition